Polar Explorer Caroline Côté and the Power of Discomfort

July 19, 2022

5 min read

After spending 18 days on the ice around Akia Island (Bylot) located in the Qikiqtaaluk region of Nunavut, Vincent Colliard, French polar explorer and Caroline Côté, professional adventurer from Montreal, are back at the starting point in the town of Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet).

It’s their first time indoors since departing on April 26th on a 475 km ski expedition without assistance.

Mittimatalik is a village in the heart of the Canadian Arctic, well nestled between valleys and fabulous mountains. It is located on the edge of the beautiful Tasiujuaq Strait. And when we inevitably plunge our gaze to the horizon, we discover the marvelous island of Bylot and its Simirlik National Park, a sanctuary for the protection of birds and the nesting grounds of the thick-billed guillemot, the black-legged kittiwake, and the greater snow goose.

I met polar explorer Vincent Colliard 3 years ago, and since then, we have become expedition partners as well as life partners. As a couple, we like to face situations that seem uncomfortable to us in an adventure context in order to grow together. Married for only a few months, we find our happiness in the present moment. Leaving with as little material as possible and for a long time makes a lot of sense for our duo.

Our desire to trace the outline of this island on skis was born from our united passions. Vincent had passed close to this place in 2018 during the La Voie du Pôle sailing expedition, where the crew had planned to cross the Arctic Ocean, linking Alaska to Svalbard via the North Pole. The last ocean never to be crossed by sailboat.

.jpg)

For my part, I had heard of this place in the exploration stories of Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian explorer who in 1903 headed towards the Arctic to try to find a route through the ice floe on Gjøa, a small vessel specializing in cod fishing. He became the first to cross the Northwest Passage. It therefore passes close to the coast in the famous Lancaster Sound on the northern side of the Bylot Archipelago.

It is an exciting place because there are also an impressive number of arctic foxes, ringed seals, narwhals, and polar bears.

Leaving the city, we were filled with strong energy and excitement. The preparation period had taken us a good week, and putting the skis on the snow allowed us to finally look back and forget how difficult traveling in northern Nunavut with all our equipment was.

The young free dogs belonging to the Pond Inlet mushers gather in front of us, giving us a puzzled look to see us dashing over the strait that will later lead us directly into the frozen Baffin Sea.

I feel like I'm part of the pack and just as happy as those off-leash quadrupeds. Suddenly I don't feel held back or taken by my sometimes suffocating daily life in the city. I feel that we are going to experience an adventure that will change the course of our lives. Without ties and being accomplices, we begin our first kilometers on the ground. I feel that Vincent is coming back to life; ice is his element.

We don't cover any significant distance in the first few days, days that quickly remind us of the body aches that come with pulling the load of our sled. Blisters in the heels, tired shoulders, tension in the knees; the repetitive song of the first days of an expedition. We must start with a slow and regular rhythm. I approach all these little ailments positively because I understand that the body's pain is a benchmark that always reminds me not to stay too long in nature. Hungry or dead tired, I have to come home to be able to leave, but I like to push this limit more and more and leave for days, weeks, and months without supplies. The comfort that urban environments provide calls me sometimes. It is good to re-enter urban environments after a long adventure, in a place where everything seems luxurious, when for weeks our house is only a small tent placed on the snow.

Tracing about 25 km per day, we progress on flat ground at the start, quietly skirting the island on the east coast, which gradually becomes a labyrinth of impressive icy structures. The decor surprises me. It's my first experience on this ice floe, very different from that surrounding Svalbard, on which I passed last year. I try to understand it. The ice fractures shrink and grow according to the wind, the tides, the currents. They are stunning. But I don't understand them. It doesn't make sense; you can't calculate how the Arctic ice behaves, and I really like being in a complicated environment, an icy labyrinth.

I am learning to recognize where to collect the ice I will use to boil my freeze-dried meals. If I pick it up in some places, it has a strong taste of sea salt. In other places, it is filled with sandy particles. I melt it in the pan, and sometimes it takes me up to an hour to get it ready and put it in large thermoses for the next day. I have a relationship of trust with the stove that I treat with care to keep it in perfect condition until we return to town at the end of the adventure. Rigor must be applied in every detail when going on a polar expedition. Broken equipment can bring us a lot of problems that can sometimes seem trivial but can become serious when we find ourselves far away without any means of communication with the outside world. That's why I bring only the most resistant equipment and clothing, those that will not let me down.

The kilometers pass as we advance at a solid daily pace. We cross a few hundred tracks of polar bears along the way but only meet the animal once during a sunny evening. It was making its way near the tent, probably to feed near the ice-free waters a few kilometers away. The meeting was powerful and meaningful. When you are lucky enough to stare into the eyes of a bear roaming free in its territory for a few seconds, you can quickly feel its full splendor and power. It's a unique moment.

This expedition charmed our spirits but also required a lot of our energy. It was complex and touched the very essence of adventure. As we progressed, I accepted that it was possible to develop an appetite for discomfort, a desire to go and see what lies hidden there. I believe there is a certain power in the discomfort we experience when leaving the zone of what we know and master – it’s a way to learn, evolve, and become better. It provides a vast territory of learning.

In summary, for a successful winter expedition:

- Take a large number of days for preparation before departure

- Study the terrain and maps

- Test your equipment in advance, especially the essentials such as the sleeping bag, the tent, the stove

- Make short-term expeditions with partners in advance

- Bring a repair kit

- Bring a complete pharmacy kit

- Let a team in town know your itinerary

- Bring suitable means of communication: Distress beacon, Satellite phone

- Bring more food in case the weather gets worse and the number of planned days is exceeded

- Bring extra clothes in case the weather conditions are colder or windier than expected (it will probably happen!)

- Bring a small notebook in which to write along the way

- Do not wear cotton that stays wet for a long time, instead opt for merino wool which gives off little odor and dries quickly

And above all, do not leave any waste!

Equipment used by Caroline

Women's Ægir Race Sailing Jacket

Women's Crew Hooded Midlayer Sailing Jacket

Women's Crew Midlayer Sailing Jacket

Women's Crew Sailing Vest

Women's Crew Fleece Jacket

Soft Rib Beanie

Women's Imperial Printed Pile Snap

Men's Panorama Printed Pile Snap

Women's LIFA® Merino Midweight 2-In-1 Graphic Half-Zip Base Layer

Women’s LIFA® Merino Midweight Graphic Base Layer Pants

Women’s Odin Mountain Infinity 3-Layer Ski Salopette

Women's Odin 9 Worlds Infinity Shell Jacket

Women's LIFA® Merino Midweight 2-In-1 Base Layer Pants

Women's LIFA® Merino Midweight Half-Zip Base Layer

Polartec Neck

HH LIFA® Merino Glove Liner

Swift HT Mittens

Unisex Outline Beanie Hat

Favorite Items

Women's Verglas Polar Down Jacket

With its impressive fill count and a strategic box-wall construction, this is the warmest down jacket we’ve ever created, with the exception of the bespoke jackets we made for the Everest expedition team. Not only does the construction eliminate cold spots, we’ve added a down-filled collar and a shock-cord to keep the cold out. With the environment in mind, our warmest down jacket uses responsibly sourced down, and the water-repellent treatment is PFC-free.

Women's LIFALOFT™ Full-Zip Insulator Pants

Designed with full side zips, these super warm and lightweight cropped pants offer easy layering above or below your pants. Originally inspired by our professional freeride partners for pre-event warmth, they have become a favorite among pro alpine skiers too. LIFALOFT™ technology ensures warmth without extra bulk or weight, while the zip construction allows for effortless on-and-off when temperatures fluctuate.

October 21, 2025 10 min read

How to plan your ski trip to Japan

Skiing Japan with Nat Segal: Hokkaido RV adventure, volcano tours, and how to thrive through a dry spell.

October 21, 2025 4 min read

Transat Café L’OR 2025: A Modern Classic of the Ocean

A double-handed Atlantic sailing epic blending grit, innovation, and coffee-route heritage.

September 29, 2025 4 min read

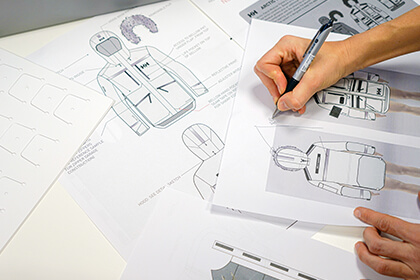

Behind the design: The Arctic Patrol Down Parka

An inside look at how Helly Hansen designed the Arctic Patrol Down Parka with insights from Arctic scientists for extreme conditions.

August 28, 2025 5 min read

Camping Under the Stars: an Open Mountain Month Experience

Part of Open Mountain Month, The Summit Sleepover is the definition of an experience money can’t buy. Dive into Andy and Anna from Roam and Create's experience at this year's edition.